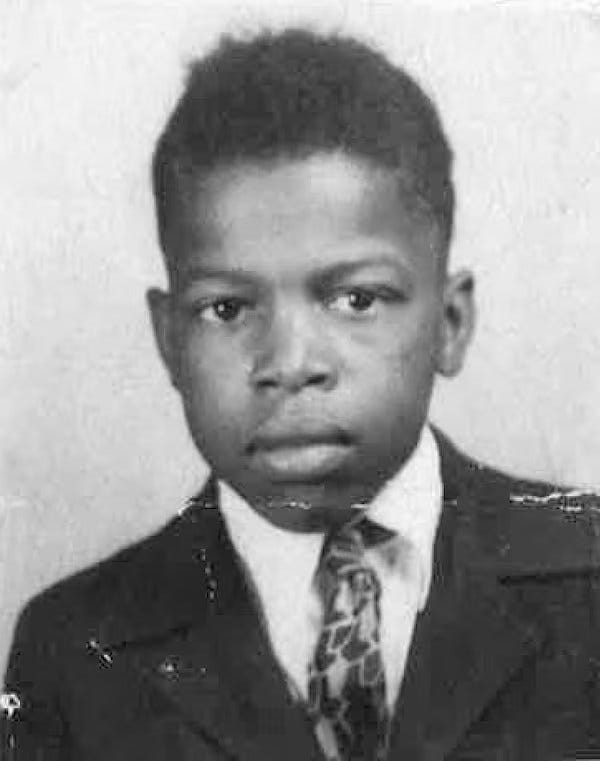

Growing up in Rural Alabama in the Jim Crow Era

Seeds of John Lewis’s activism can be traced back to his childhood in Pike County, Alabama, near the town of Troy. Lewis was born on February 21,1940, the third of 10 children. He grew up on a cotton farm where his parents and, earlier, his grandparents worked long hours for little pay as sharecroppers - in the early 1940s, the average sharecropper family's income was less than 65 cents a day.

As a child, Lewis could tell things weren’t right from the omnipresent “Whites Only” signs on the nicer drinking fountains, restrooms, waiting rooms, hotels, telephone booths, restaurants, and cemeteries - not to mention the “Whites Only” sections of buses, movie theaters, and neighborhoods – and segregated schools. Segregation was so ingrained in Alabama that Bibb Graves, Governor of Alabama from 1927 to 1931 and 1935 to 1939, was the Grand Cyclops of the Ku Klux Klan when he was first elected.

Lewis was 15 when he was first inspired by Martin Luther King, Jr. delivering a sermon on the radio. Around the same time, Lewis was riveted by the activism of Rosa Parks. The 12/5/1955-12/20/1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott, sparked by Parks' courageous refusal to give up her seat to a white passenger and subsequent arrest for violating the city’s segregation laws, motivated Lewis to learn more about the fight for civil rights.

When he was 16, Lewis visited the public library to check out books. The library is for “Whites only, not for Coloreds,” the librarian told him. That was a tipping point for Lewis, when, despite his parents’ warnings, his thoughts turned to action. From then on, Lewis told himself, “Whenever you see something that is not right and not fair, you have a moral obligation to continue to speak up, to speak out.

The heinous murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till on August 28, 1955 deepened Lewis’ resolve. Horrific images of Till's mutilated body, and the subsequent acquittal of his killers, affected Lewis deeply, catalyzing his involvement in the Civil Rights Movement. He viewed Till's murder as a call to fight for racial equality and justice, later saying, "It could easily have been me."

John Lewis first met Martin Luther King, Jr. in March 1958. King had invited Lewis to Montgomery after being impressed by a letter Lewis wrote to him expressing interest in the civil rights movement. Upon meeting the then-18-year-old Lewis, King addressed him: “So, you are John Lewis, the boy from Troy.” Little did they know that the boy from Troy would grow to become a legend of the civil rights movement.

John Lewis’s “Note to Self” as a child, including a preview of what’s to come: [

The Nashville Sit-Ins

After graduating in 1957 from a segregated high school in rural Alabama, John Lewis moved to Nashville, Tennessee, where he graduated from American Baptist Theological Seminary in 1961 and was ordained as a Baptist minister. Two years later, he earned a BA in Religion and Philosophy from Fisk University.

Lewis’s plans of becoming a Baptist minister were derailed, however, by his involvement in the Civil Rights Movement in Nashville. But his religious studies certainly didn’t go to waste. Discussing the religious, ethical and tactical basis of nonviolent civil disobedience with fellow students Jim Lawson, Diane Nash, James Bevel, Bernard Lafayette, and later-to-become DC’s Mayor Marion Barry, grounded Lewis’s activism in his Christian faith and love.

Rev. James Lawson trained students from Nashville’s four Black colleges in the philosophy and tactics of nonviolent direct-action. Soon, Lewis was among nearly 500 students waging nonviolent sit-ins at segregated lunch counters and filling the jails of Nashville with their freedom songs. Sometimes, they would simply be sitting quietly with their books, doing their homework, when a segregationist would come from behind and hit them, spit on them, pour ketchup on them, or grind out a cigarette on them. Even when met with violence, the students’ commitment to nonviolence never wavered.

Lewis recalled, “When I look back on that particular period in Nashville, the discipline, the dedication and the commitment to nonviolence was unbelievable.”

Shortly after the sit-ins started, the students were warned that if they continued, the backlash could become increasingly violent. Despite the warnings, they remained committed. Although afraid, they felt they “had to bear witness.” Lewis distributed “dos and don’ts”: sit up straight; don’t look back; if someone hits you, smile, etc. At the end, he later recalled, the handout “said something like, ‘Remember the teachings of Jesus Christ, Ghandi and Martin Luther King: May God be with you.’“

The Nashville sit-ins Lewis helped organize and participated in took place from February 13 to May 10, 1960, when lunch counters in downtown Nashville were finally desegregated. Although an earlier sit-in took place in Greensboro, North Carolina, on February 1, 1960, it was the Nashville students who gave impetus to the concept of nonviolent direct action and became leaders in the Civil Rights Movement.

Lewis and the other activists felt like what they were doing was in keeping with the Christian faith. “Something just sort of came over us and consumed us. And we started singing ‘We Shall Overcome’,” which became a key anthem in the Civil Rights Movement.

In this video, John Lewis reflects on the students’ training in and commitment to nonviolent direct-action, the risks they were willing to take, and what they endured for the betterment of society:

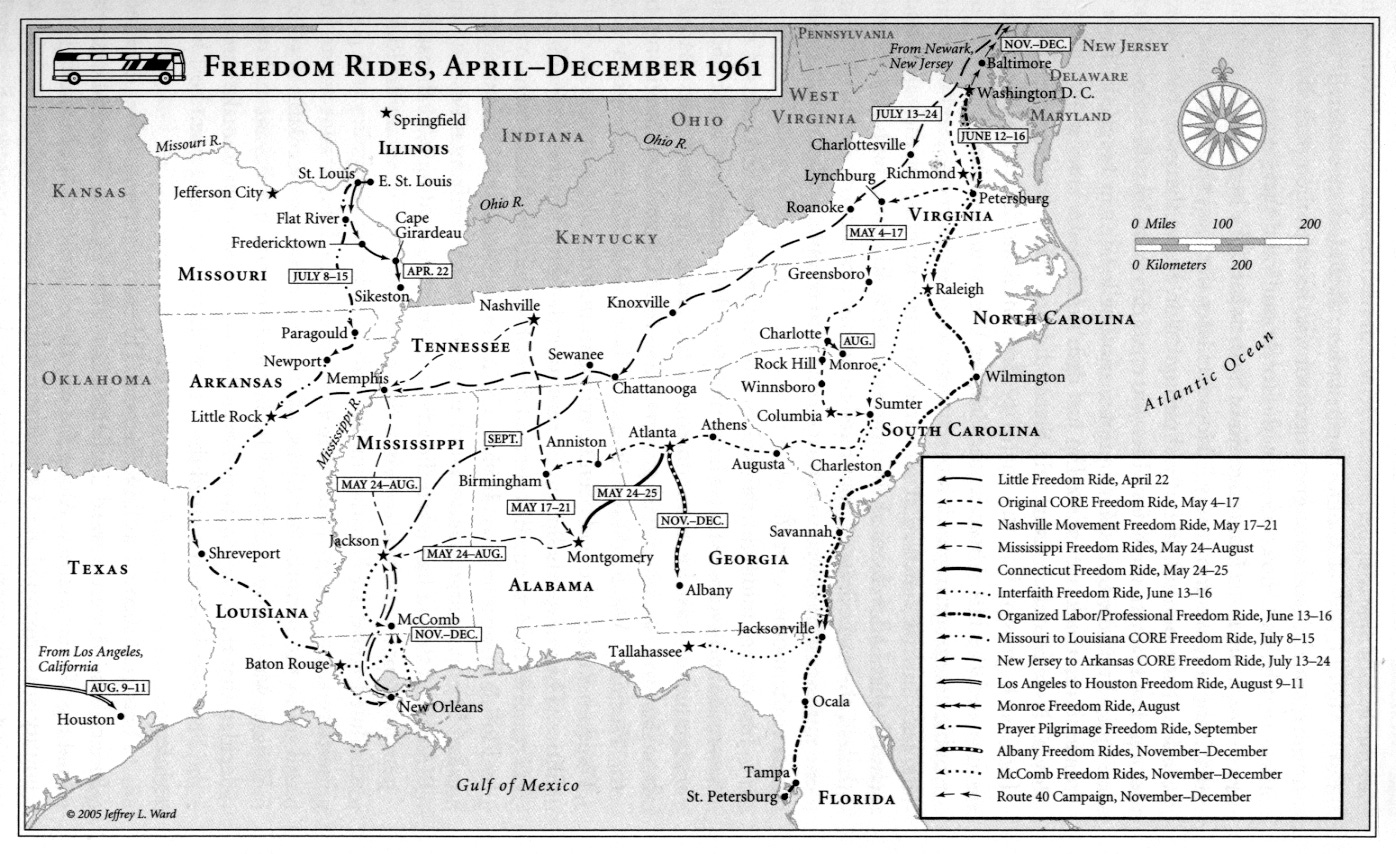

The 1961 Freedom Rides

On May 4, 1961, 13 passengers – including 21-year-old seminary student John Lewis – boarded two buses in Washington, DC, bound for New Orleans. Their goal? Challenge and expose state laws that continued to enforce segregation on buses and in bus terminals despite the 1960 Boynton v. Virginia U.S. Supreme Court ruling prohibiting the segregation of interstate travel.

This was the first Freedom Ride organized by CORE (Congress of Racial Equality).

Their first confrontation with violent segregationists took place in Rock Hill, South Carolina. As the Freedom Riders tried to enter a “whites-only” waiting room in Rock Hill’s Greyhound terminal, John Lewis and others were assaulted by a mob of young white men.

The violence escalated further on a highway outside Anniston, Alabama, when one of the Freedom Ride buses was firebombed. When the Freedom Riders escaped the burning bus, they were attacked by a mob of white segregationists.

John Lewis was also on the Freedom Ride from Birmingham to Montgomery. Upon arriving at the Montgomery bus terminal, Freedom Riders were brutally attacked by a mob of over 200 Klansmen. John Lewis, William Barbee, and Jim Zwerg were beaten unconscious.

On May 23, John Lewis and Martin Luther King Jr. held a press conference in Montgomery, announcing that the Freedom Rides would continue despite the violent attacks they had suffered. In the photo, below, bandages can be seen on Lewis’s head from the beatings he had endured.

Hundreds of volunteers from across the country traveled to Mississippi to support the effort, committing their lives to nonviolent direct-action. That summer, a total of about 436 people – mostly ages 18 to 30 – participated in 60+ Freedom Rides. More than 75% were arrested.

About 300 Freedom Riders, including John Lewis, were sent to Mississippi’s notorious State Penitentiary at Parchman after being arrested in Jackson, Mississippi, for trying to use a “Whites Only” restroom and charged with “breach of peace.” They were incarcerated under harsh conditions for 37 days.

Many Freedom Riders – including Lewis – adopted a resistance tactic called "Jail, No Bail," refusing to pay bail. Staying in jail or prison enabled them to generate more media coverage, nationally and internationally, about the severity of segregation and discrimination African Americans continued to face in the South.

Finally, the newly-elected Kennedy Administration pressured the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to act. In September, the ICC required that interstate bus operators remove all "whites only" signs from bus terminals and report any interference with the 1960 Supreme Court ruling banning segregation on interstate travel. Violators were held accountable in federal courts.

The whole world had watched in horror as a Freedom Ride bus burst into flames outside Anniston and hundreds of young men and women, Black and white, from all over the country, were beaten and bloodied by mobs of cursing Klansmen.

In the end, SHAME spurred the federal government to finally take a stand, do what was right.

In this video, John Lewis explains the rationale of the Freedom Ride and what the riders endured

This video is harder to watch:

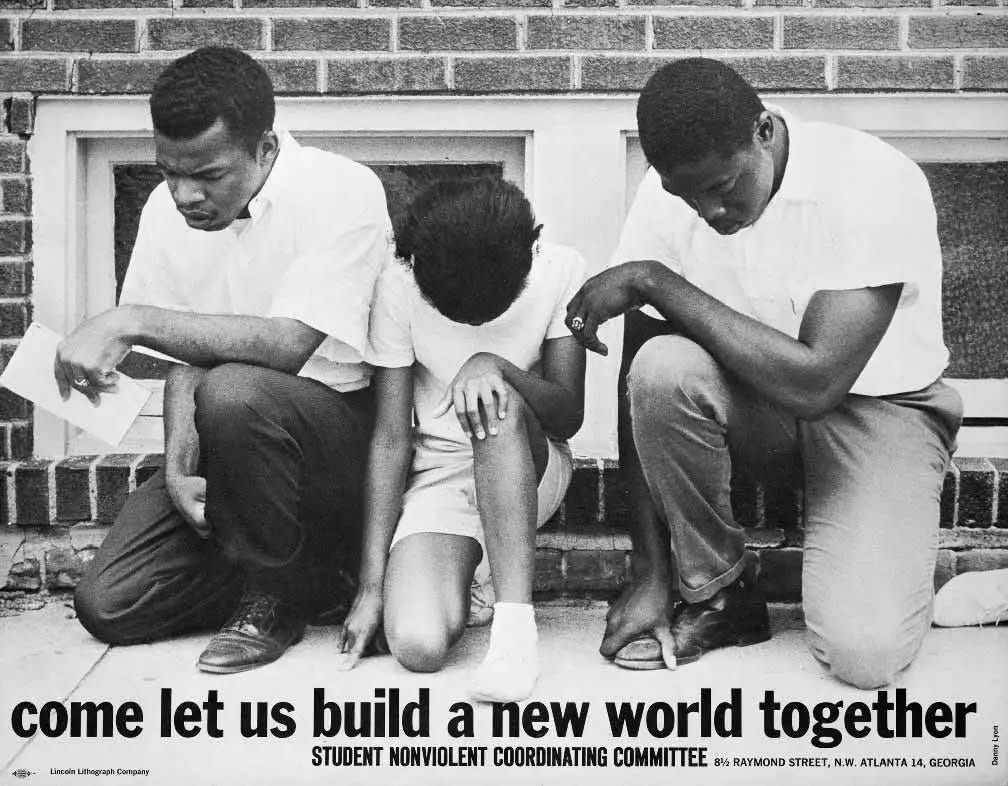

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

Founded in 1960, SNCC focused on empowering young people, primarily Black college students, in nonviolent direct-action against Jim Crow segregation and racial inequality in the South. During Lewis’s tenure as Chairman, 1963-1966, SNCC led or collaborated on numerous campaigns and actions, including:

March on Washington (1963): 23-year-old Lewis was the youngest organizer of the 250,000-person March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. By then, he was also the youngest member of the “Big Six” leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, along with Martin Luther King Jr., James Farmer, A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, and Whitney Young. After MLK Jr delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, Lewis gave a powerful speech of his own, calling for immediate action on civil rights legislation. (Tomorrow's post will focus on this event.)

Voter Registration Drives: SNCC trained a new generation of civil rights activists to focus primarily on Mississippi and Alabama, where Black voters faced the most barriers and intimidation. SNCC volunteers were threatened, beaten, arrested, even murdered by white segregationists including Klansmen. Widespread media coverage of the attacks helped SNCC expose nationwide the systemic disenfranchisement of Black voters in the South while challenging entrenched norms that privileged white people at the expense of Black people.

Mississippi Freedom Summer (1964): Collaboratively, SNCC and CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) bused more than 700 white student volunteers down from the North to help Black Mississippians register Black voters and establish Freedom Schools. While investigating a church burning and beating of church members by the Ku Klux Klan, a Neshoba County Sheriff arrested a Black Mississippian and two white Northerners with SNCC – and then released them to his fellow Klansmen who murdered them.

Selma to Montgomery March (1965): State troopers cracked down on the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, twice. John Lewis led the voting rights activists the first day, March 7, later called “Bloody Sunday” due to brutal attacks on protestors on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. 58 people were hospitalized. Lewis suffered a fractured skull. The second leg of the march was also halted. The third was aided by a federal court order charging federal troops with protecting marchers until they reached Montgomery.

Under John Lewis’s leadership, SNCC – and the hundreds of thousands of everyday people who joined Lewis’s rallying cry for social and political change – helped awaken America's consciousness and conscience to the pervasiveness of racial inequity and injustice in the South and played a vital role in paving the way for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In May of 1966, Lewis was replaced as Chair of SNCC by civil rights activist Stokely Carmichael. While initially involved in SNCC's nonviolent activism and interracial alliances, Carmichael later advocated for a more separatist "Black Power" ideology, emphasizing Black self-determination and empowerment.

After leaving SNCC, Lewis directed the Voter Education Project. In 1977, he was appointed by President Jimmy Carter to direct ACTION, a federal agency that preceded AmeriCorps and oversaw more than 250,000 volunteers

In this video, John Lewis reflects on “Bloody Sunday”

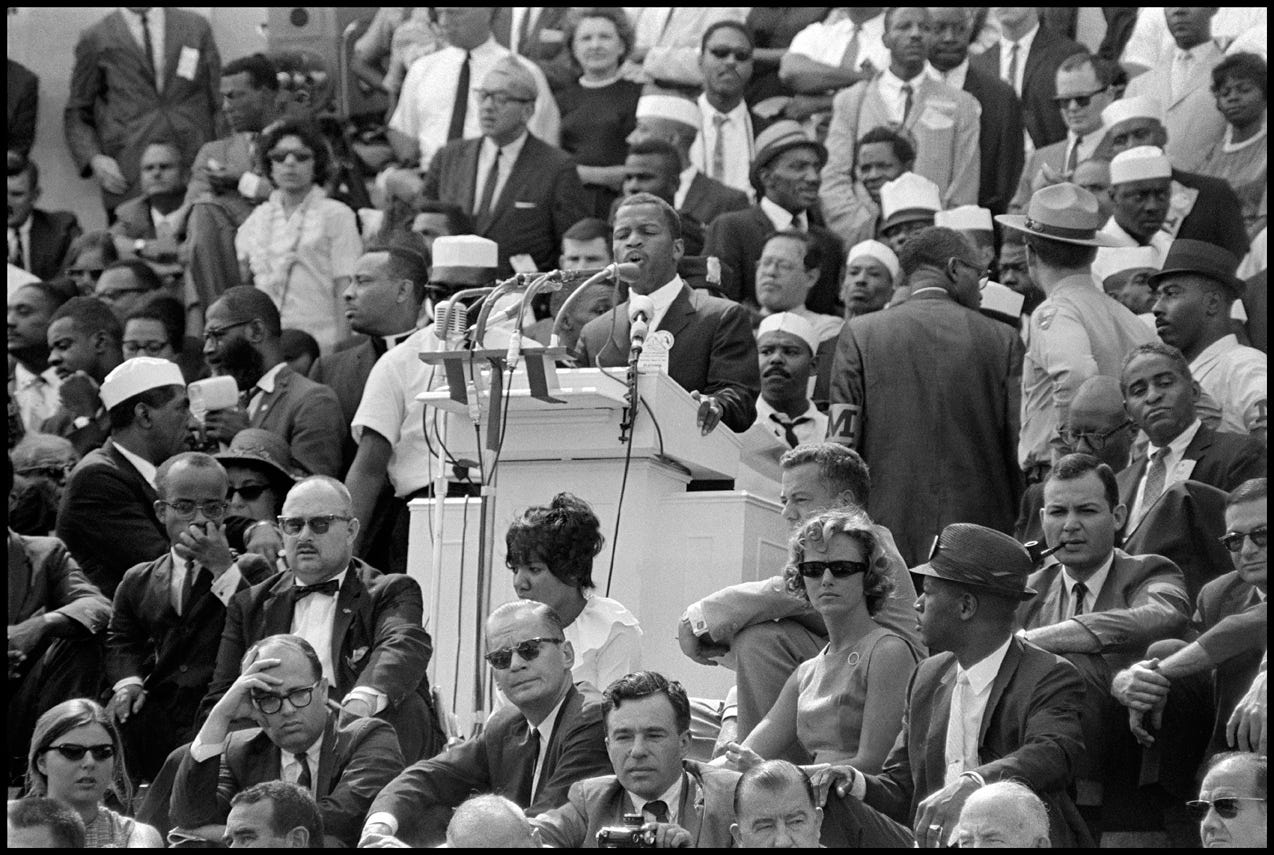

August 28, 1963, March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

The 250,000-person March on Washington was a resounding success, so most critics fell silent after the event All the more reason to identify and reflect on the opposition that tested the moral courage and steely conviction required to pull off such a risky venture during such a volatile time in U.S. history.

Leading up to the March, President Kennedy was supportive, publicly. Behind the scenes, his administration feared the event would incite violence that would erode public support for the Civil Rights Movement and undermine Congressional support for the Civil Rights Act, which he had introduced on June 11. He knew that many Congressional members were looking for any excuse to vote NO.

Opposition came from within the movement, too. Malcolm X felt the event had been hijacked by white liberals and become a symbol of "integration" versus an expression of genuine Black frustration with racial inequality. And Stokely Carmichael wasn’t the only member of SNCC, which Lewis became Chairman of two months before the March, who believed the event kowtowed to President Kennedy and other white leaders at the expense of grassroots efforts to build genuine Black political power.

Several Black female organizers were concerned about the gender inequality within the Civil Rights Movement. Their voices – and recognition of their contributions – were largely excluded from the main program at Lincoln Memorial. And only one woman, Myrlie Evers, widow of slain civil rights leader Medgar Evers, was included in the official delegation that met with President Kennedy after the March.

Predictably, Southern Congressional members who opposed the Civil Rights Movement opposed the March. The core principle of the event – equal rights for all – was at odds with their fundamental beliefs. South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond tried to undermine the credibility of the March by accusing organizer Bayard Rustin, an openly gay man, of being a Communist and a "pervert.” At the same time, Southern media coverage of the March often minimized concerns raised by organizers.

American Nazi Party leader George Lincoln Rockwell tried to organize a counter-protest at the base of the Washington Monument – without a permit. He had expected thousands of angry segregationists to join him. 74 showed up, fenced in by 200 policemen and National Guard MPs. When one of Rockwell’s supporters started to give a speech, he was arrested. Rockwell left, exclaiming that he was ashamed of his race.

The Ku Klux Klan also posed a threat. A private plane carrying Imperial Wizard of the United Klans of America (UKA) Robert Shelton crashed while departing Alabama for Washington, DC – the day before the March! At the time, Shelton’s Klan was the largest KKK faction in the world with an estimated 26.000 to 33,000 members. The UKA was also the most violent Klan organization.

In the end, President Kennedy was pleased and proud. Despite the barrage of opposition and threats faced by the “Big Six” civil rights leaders, the March mobilized more support for to the Civil Rights Movement and helped pave the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

But …

Right after the March, as if a warning, a photo of a cross-burning with 2,000 KKK members addressed by Robert Shelton aired – see news clip below. And two weeks after that, on September 15, Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church – a meeting spot for civil rights leaders – was bombed, killing four Black girls and injuring about 20 more congregants.

Each win, it seems, was followed by a profound loss.

In this video, John Lewis reflects on the March, his speech, and the role of compromise in building unity: [http://www.pbssocal.org/.../rep-john-lewis-remembers-the...](http://www.pbssocal.org/.../rep-john-lewis-remembers-the...)

The Conscience of Congress

John Lewis served Georgia’s 5th Congressional District for 17 distinguished terms, from 1987 until his passing in 2020. He was the second Black American to be elected to Congress from Georgia since Reconstruction and the only former major civil rights leader to continue his fight for justice in the halls of Congress.

Despite representing the most Democratic district in Georgia and being among the most liberal members of Congress, Lewis was known for bridging political divides. Since his first sit-in in Nashville, his overarching goal was to create a "beloved community” rooted in equity and inclusion. “It begins inside your own heart and mind, because the battleground of human transformation is really, more than any other thing, the struggle within the human consciousness to believe and accept what is true… to truly revolutionize our society, we must first revolutionize ourselves. We must be the change we seek if we are to effectively demand transformation from others.”

Until the end, John Lewis waged “good trouble,” lending moral certitude to each action.

In 1996, Lewis delivered an impassioned speech against the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). He compared the opposition to DOMA to the fight against Jim Crow laws, arguing that what was the majority view back then was not always correct. He engaged in civil disobedience against Trump’s “zero tolerance” immigration policies, marching through the streets of Washington, DC, under the banner "Families Belong Together." He led House Democrats in a sit-in, occupying the House floor for nearly 26 hours to demand action on gun control legislation. After Clinton lost, in 2016, he refused to attend Trump's inauguration, explaining that his absence was a "form of dissent." Shortly thereafter, he protested among 2,000 people outside Atlanta Airport to protest the ban and detention of 11 airplane passengers taken into custody the previous day, spurred by Trump’s “Muslim Ban.”

After revealing his diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, in December 2019, Lewis said, "I am going to fight it and keep fighting for the Beloved Community… We still have many bridges to cross." Three months later, in the thick of the pandemic, he made a surprise appearance at the annual reenactment of the Selma to Montgomery march marking the 55th anniversary of the brutal attack on voting rights marchers at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965, including then-25-year-old John Lewis. Surrounded by marchers, Lewis urged younger generations to carry on the work of his generation of civil rights activists.

Lewis's outspoken support for LGBTQ+ rights wasn’t always popular, including within the Congressional Black Caucus. In 2020, his funeral motorcade stopped briefly in front of the Human Rights Campaign DC headquarters, a symbolic recognition of his support for LGBTQ+ rights throughout his career.

As Obama said, in 2011, when he awarded Lewis the Presidential Medal of Freedom, “Generations from now, when parents teach their children what is meant by courage, the story of John Lewis will come to mind — an American who knew that change could not wait for some other person or some other time; whose life is a lesson in the fierce urgency of now.”

Memorializing John Lewis (February 21, 1940 – July 17, 2020)

John Lewis taught us – and his legacy continues to teach us – about using our voice to mobilize support for those in harm’s way, about responding bravely and with conviction in the face of injustice, and about integrity, remaining steadfastly peaceful and nonviolent while fighting for a cause.

Whether as the (grand)son of sharecroppers on a cotton farm in rural Alabama or as the young boy who knew there was something wrong with “Whites Only” and “Coloreds Only” signs or as the teenager who felt Emmett Till could’ve been him or as the aspiring preacher who waged countless sit-ins in Nashville or as one of the 13 original Freedom Riders who refused to let a fractured skull stop him from continuing to challenge segregated interstate bus transportation or as the Chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee who prioritized the empowerment of young Black southerners or as the youngest member of the “Big Six” leaders of the historic March on Washington or as the 17-term Congressional representative for Georgia’s 5th District who continued to put his body on the line for what was right and was arrested a total of 45 times for nonviolent civil disobedience, John Lewis never stopped envisioning – and sacrificing for – a more equitable and just America.

In the heat of this documentary moment in history, Lewis would say, as he often did, “Our children and their children will ask us, ‘What did you do?’” Following that train of thought, each of us must ask ourselves: What have I done, what sacrifices am I willing to make, to combat the re-emergence of white supremacy (which is all too familiar to Black people who have never had the luxury of being able to tune out fascist rhetoric or retreat from the fight)? What will I tell my children and their children? To (potential) allies, he said, “Take a long, hard look down the road you will have to travel once you have made a commitment to work for change.” For he believed that the struggle for change was a lifelong commitment, requiring personal risk, tireless dedication, and collective discipline – across generations.

Tomorrow, we will stand on the shoulders of Civil rights activists who risked everything while fighting for, John Lewis would say, the “Beloved Community,” in which everyone is treated with dignity and respect. We will call out Trump’s whitewashing of uncomfortable Truths – slavery, discrimination, and how far our nation has fallen from its ideals of “liberty and justice for all” – to glorify and propagandize U.S. history, to “Make American Great Again” – for white folk, ‘cause it damn sure never was for anyone else.

After our rally, in DC, we will march to Black Lives Matter Plaza, which Trump erased right after his inauguration, and then continue on to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, which we will encircle in silent, candlelit reverence for the ancestors – to whom we are all indebted.

Below, please share how you or your community will honor the life and legacy of John Lewis for 07/17/2025 or how his life story has emboldened your own willingness to get into "good trouble" for the greater good, for future generations.

Sent in and written by Erika Berg

I will be going to a rally honoring John Lewis in my town tonight.

Erika Berg you have written a glorious tribute to John Lewis and an inspiring call to action. Thank you!